For early 20th-century furniture designers, a tube of steel possessed something akin to the allure that a lump of lead had for medieval alchemists. They were confronted with a difficulty analogous to the one that had bedevilled the first chemists, for no one could quite figure out how to transmute cylinders of the lustreless stuff into something that promised to revolutionise furniture design. That was until a young Hungarian by the name of Marcel Breuer bought himself a bicycle. The story goes that as he was showing off his new Adler pedal bike to an architect friend, the latter, aware that his pal, a recent Bauhaus graduate, was on the look-out for a new medium in which to work, drew Breuer’s attention to the tensile tubes of steel that served as the cycle’s handlebars: ‘Did you ever see how they make those parts? How they bend those handlebars?’ queried the friend. ‘You would be interested because they bend those steel tubes like macaroni.’

Breuer didn’t need his friend to tell him that steel’s strength and tensility meant it held promise for furniture design, especially for cantilevered pieces where material strength is all-important. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had already brought to Breur’s attention a chair by the Dutchman Mart Stam that supported itself using lengths of gas pipe. An assortment of hobbyists had also knocked up early versions of a steel-framed chair sans rear leg supports. However, these tended to be hefty Heath Robinsonesque contraptions and anything but decorative. What had escaped Breuer’s notice and what the friend was hinting at was that the cylindrical steel from which the handlebars were fashioned was materially different from the stuff used hitherto. It was seamless and possessed an elastic quality, and therefore could be bent without splitting. This meant that a single length might be easily twisted into, say, a chair leg. His imagination fired by his pal’s observation, Breuer got to thinking that the marriage of strength, lightness and decorativeness that had eluded his fellow designers might be achieved with the same metal used to make his cycle’s steering apparatus.

The encounter with the Adler handlebars came at a propitious time for the 23-year-old Breuer. He had only recently returned to the Bauhaus to head up the school’s carpentry department and was on the lookout for a project that would allow him to announce himself. A reductionist re-imagining of the classic gentleman’s club seat, one that made use of a metal that had so far confounded his contemporaries, appealed to him on many levels. Overstuffed and bombastic, the club seat was crying out, in Breuer’s view, not just to be simplified but democratised too. Where its original was a pricey piece of furniture and a fixture in the toffish gentleman’s club, Breuer’s pared-down version would be an inexpensive, machine-made seat that the masses would use to furnish their sitting rooms.

The problem was he wasn’t sure where he might source the metal that would allow him to realise his vision. The Adler bike company naturally suggested itself, and so he appealed to them to send him lengths of their tubular steel. However, when he told them that he intended to nickel plate the steel and use it as a chair frame, they demurred. At the time, heavy-duty items such as car bumpers and bicycle parts were nickel-plated, not decorative household items. Not discouraged, Breuer next turned to the Mannesmann steel company, suppliers of much of Germany’s steel and the people who had developed the technique that allowed for the manufacture of the seamless type of the metal. The Mannesmanns were happy to oblige and sent him some of their cold-drawn steel tubes so that he might knock up his prototype.

Breuer promptly retreated to his workshop at the Bauhaus. It was here that he and a local plumber got to work on bending and welding the tubes into a shape that resembled a chair frame. He worked and reworked his material and had the plumber join the twisted tubes, but the ‘elastic and transparent’ chair he had in mind always seemed to elude him. The prototypes were unwieldy and stiff, and despite the fact the legs were nickel-plated, their joins betrayed obvious weld marks in places. It was at this point that he recognised that his chair’s geometry needed to do more of the heavy lifting. By using a single piece of tubular steel, bent so that it acted as both the chair’s arm and leg, he could obviate the need for welded braces and at the same time allow the piece to shed some of its bulk. However, this unbuttressed set-up ran the risk of the chair toppling over or sagging as the sitter made himself comfortable.

Breuer needn’t have worried; the frame did bear up. And yet he couldn’t shake the feeling that the chair’s slimmed-down aesthetic lacked a certain something. His prototype seemed a little too sober and forbidding as a piece of furniture. He felt he’d perhaps gone too far with the chair’s awkward angularity and fabric finish that was distinctly lacking in anything that approached plushness. The marriage of cold steel and plain-looking fabric might work as an intellectual exercise in pushing design boundaries, but he began to suspect no one would choose to use it as a chair in a practical setting. Breuer later acknowledged his doubts when he described his chair as his ‘most extreme work both in its outward appearance and in the use of materials…the least artistic, the most logical, the least 'cosy' and the most mechanical’. This lack of cosiness owes something to the influence of the De Stijl movement, an austere approach to art and design that Breuer found particularly congenial in the early part of his career. De Stijl originated in the Netherlands with the artists Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. Their influence on Breuer’s design can be felt particularly in the stark geometry of the intersecting lines and planes used in the layout of the chair’s frame and the unfussy finish of its monochrome canvas upholstery.

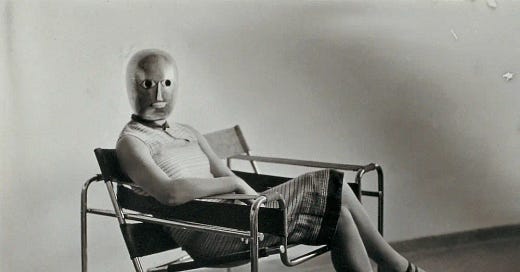

Breuer remained unconvinced by his chair until fellow Bauhausler Wassily Kandinsky took a liking to it. In fact, the abstract artist was so taken with the chair that he had Breuer gift it to him. The version that charmed Kandinsky consisted of just nine pieces of slimline tubular steel, each arranged so that the sitter’s flesh would never press up against the cold steel when fully sedentary. The chair’s cocked seat described a proud angle that stubbornly refused to lie parallel with the floor and was positioned to give the sitter’s upper leg maximum support. The angled seat relieved the pressure that a more horizontal support would apply to a sitter’s lower limbs. Where the frame had to be welded, the joins were hidden from view on the underside of the seat and the welded struts on the chair’s legs, plated in chrome - not nickel - to cut costs, were capped. Breuer upholstered his chair with eisengarn thread, a hard-wearing, easy-clean fabric that was used to make belts and shoelaces for soldiers in the Kaiser’s army. The sparse layers of canvas that served as the back and seat were neatly suspended from the frame and became taut as they hugged the body close to accommodate the sitter.

The Wassily chair was one of the first pieces manufactured by Standard Möbel, a company Breuer and fellow Hungarian Kálmán Lengyel created to market their tubular steel furniture. How this tallied with Breuer’s intention of having his chair mass-produced isn’t clear. The partnership couldn’t be anything more than an artisan affair. However, one of the early issues attracted the attention of Thonet, whose founder, Michael Thonet, had done for wood what Breuer had for steel: he had found a way to bend it (using steam) so that it could be moulded into a piece of furniture. By the early 1900s, Thonet had more than 50 factories throughout the Habsburg empire. Here, they mass-produced their bentwood designs using standardised parts, an early application of Fordism to furniture manufacture. Breuer realised that if his design was to find its way into the proletarian parlours, it would be best to turn production over to someone with the means to mass produce it. Thonet subsequently tinkered with the back support and added a crossbar to the base to compensate for the removal of a transverse underneath the seat. They continued to manufacture the chair throughout the inter-war years, but it fell out of fashion after the second world war.

It was only in the 1960s the chair was brought back into production, when Dino Gavina, an Italian furniture maker, convinced Breuer to let him manufacture it at his factory in Foligno. Until then the chair was usually referred to as the Breuer club seat or the model B3. That was to change when Gavina learnt that Breuer had given his prototype to the artist Wassily Kandinsky. Not a man to miss a marketing opportunity, Gavina started to champion the chair as the ‘Wassily’ in the company’s marketing literature. When Gavina filed for bankruptcy in 1968, its current manufacturer, Knoll, applied for trademark protection of the name Wassily and has used the appellation ever since. The Knoll version of the chair remains faithful to Breuer’s design. The steel frame continues to be chromed, but if the buyer’s feeling flush it can be plated in 18-carat gold. Where Breuer’s original blueprint called for the chair to be upholstered in a simple black fabric, today it comes in one of 27 different shades of Spinneybeck leather, haired hide and natural canvas. The Knoll version of the Wassily chair retails for approximately £1,700 ($3,000).

A Knoll Wassily chair measures: W79cm D69cm H73cm. The seat height is 42cm.